Brook Andrew in the archives

2 Dec 2025

Brook Andrew (Wiradjuri/Ngunnawal) has spent more than thirty years researching in museums and collections, including the British Museum, the Smithsonian, The Pitt Rivers Museum Oxford, Wereldmuseum and Australian state libraries, among many others. He collects postcards, photographs, glass slides, racist caricatures, scientific documents, massacre letters, dendroglyph imagery and cultural objects, treating them as ngawal murrungamirra, (Powerful Objects), rather than passive artefacts.

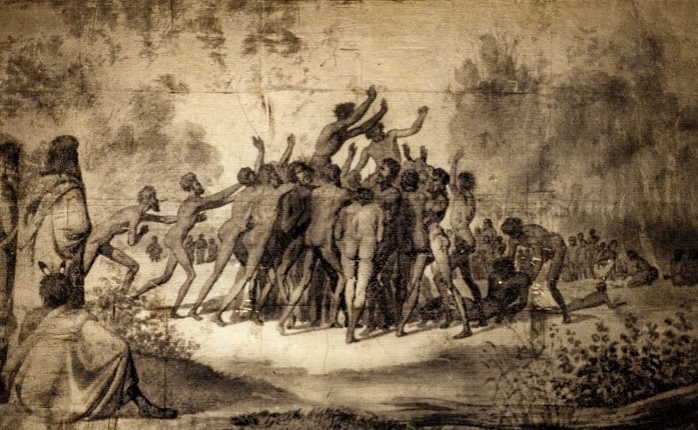

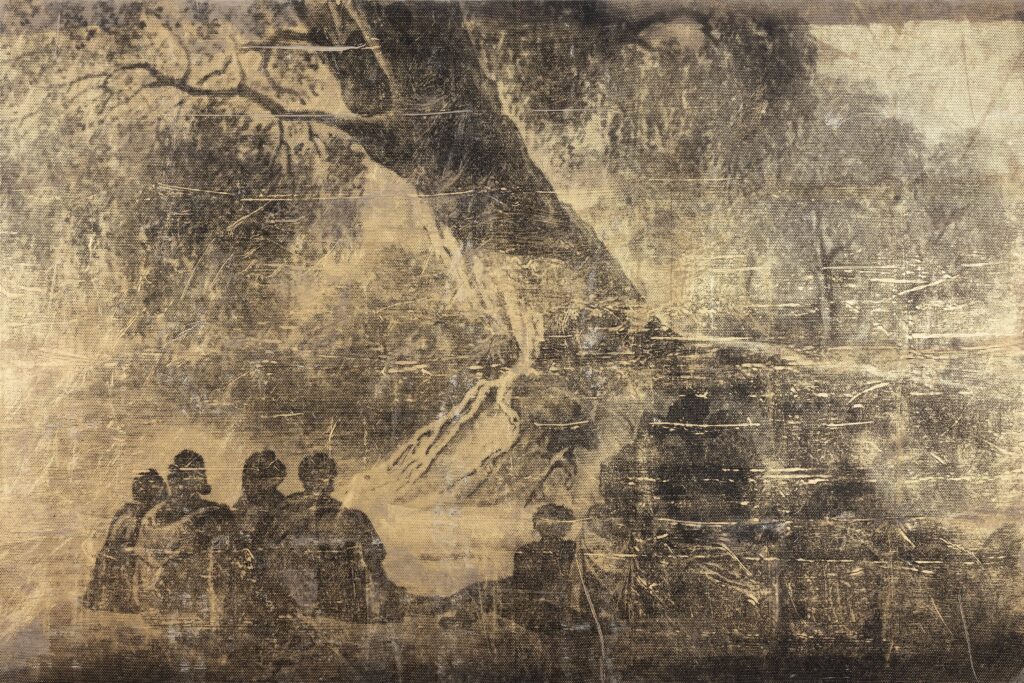

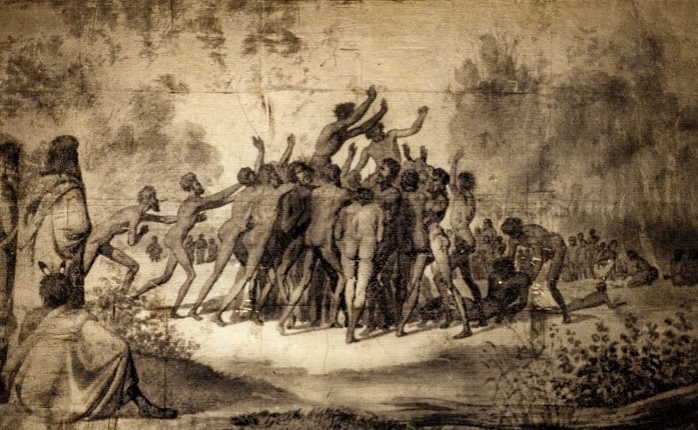

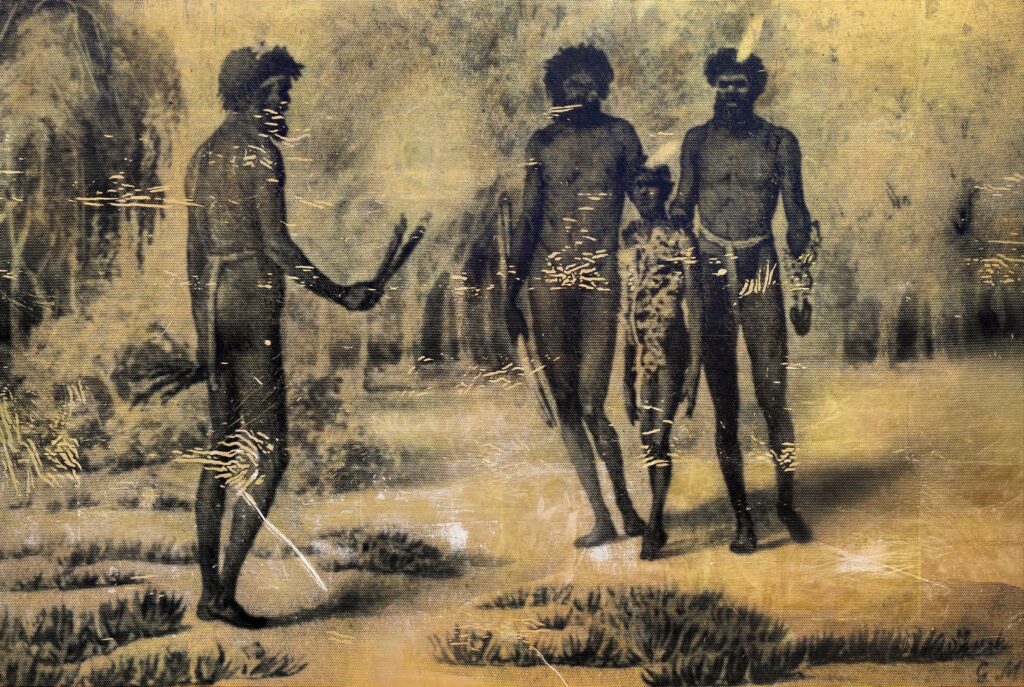

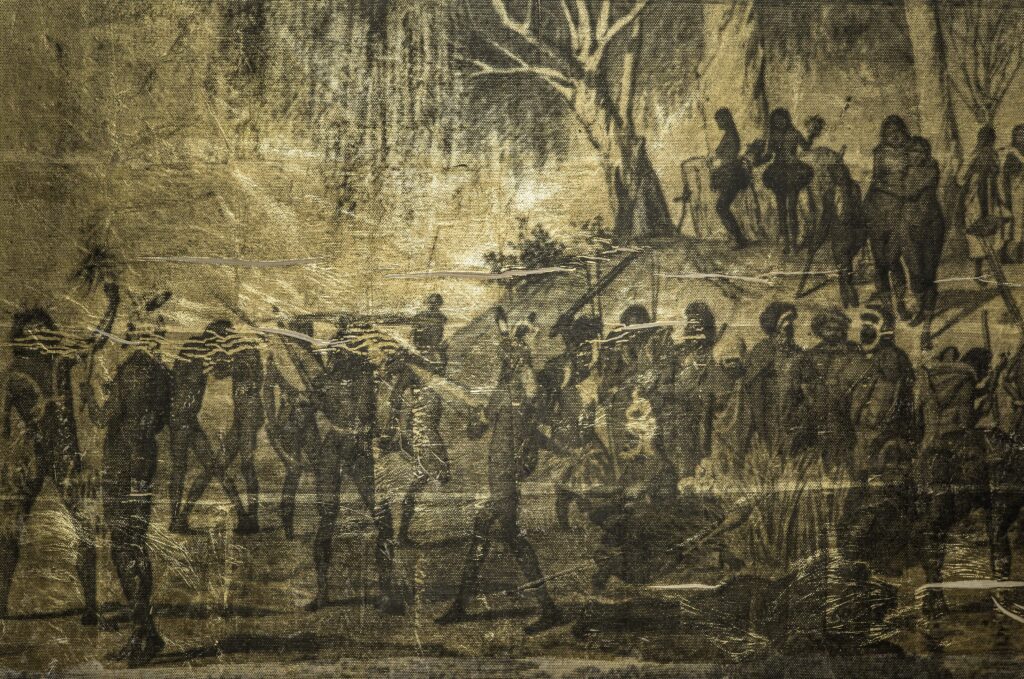

His AUSTRALIA I–VI series (2012–14) emerges from this long-standing and deep archival work. Here, six large-scale works re-present nineteenth-century scenes illustrated by German artist Gustav Mützel, who never visited Australia but translated German naturalist and ethnographic illustrator, William Blandowski’s 1856–57 Murray–Darling Basin sketches into tiny albumen prints. Only a few copies remain in Europe, and the image inspiring AUSTRALIA I survives as a small print in the British Museum.

We speak with the interdisciplinary artist, writer, curator and researcher about his time in the archives, his uneven discoveries and interventions.

Brook Andrew, AUSTRALIA I, 2012, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

Where does your interest in the Australian ethnographic archive originate?

My interest comes from growing up inside Wiradjuri life while simultaneously witnessing how absent my own people were from public Australian memory. As a child and later, at art school, I spent a lot of time looking through family photographs — images that held a completely different world to the one represented in our history books, newspapers and museums. This contrast was jarring, and it made me want to understand how those absences came to be.

When I first entered ethnographic archives, I saw not only omission but also violence, in the classifications, the pseudo-science, the cold categories, the voyeuristic fascination. Yet, I also saw complex and sometimes even respectful depictions, such as Blandowski’s sketches, which — although framed by colonial intent — presented Aboriginal people with more dignity than many of the grotesque caricatures made by explorers and amateur ethnographers. Those contradictions fascinated me. They revealed how representation is never neutral. I realised early on that these archives — these tangled repositories of trauma and curiosity — needed to be interrogated. So, my work in archives began as both a personal and political necessity — an attempt to understand how others had tried to define us and to reclaim the right to define ourselves.

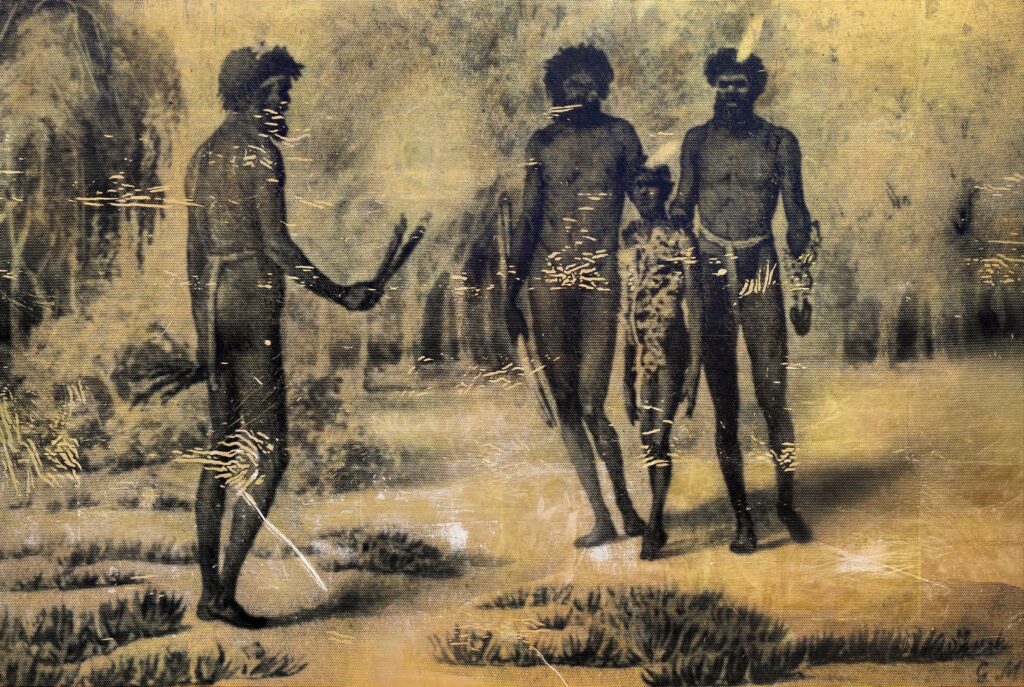

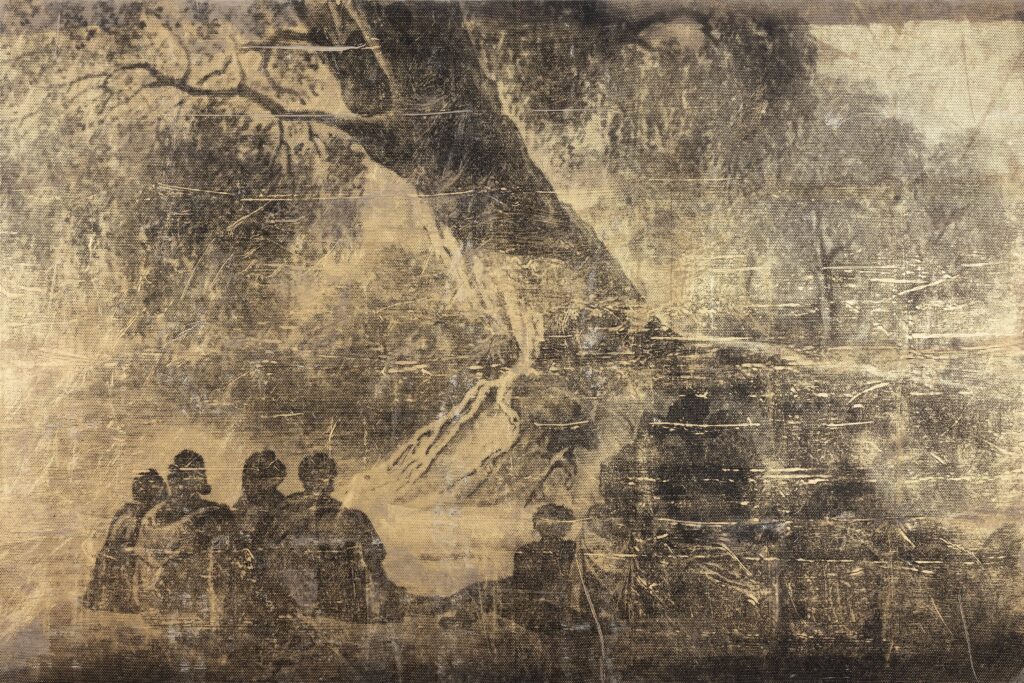

Brook Andrew, AUSTRALIA II, 2014, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

What is your process with historical materials?

My process is grounded in intuition, emotion and research. When I move through archives, I treat objects and images as living entities — ngawal murrungamirra, Powerful Objects. I don’t approach them simply as data; I listen for what pulls me toward them. Sometimes it is an item’s beauty or fragility, sometimes the weight of its history and sometimes its sheer wrongness — its cruelty, racism or distortion. I follow that tension. I gather materials much like I gather memories — slowly, rhythmically allowing them to reveal what they need to. This means that my practice is not just academic; it is embodied. I hold objects, I breathe the dust of rooms where they have slept for decades, and I imagine the hands that created them or the circumstances under which they were taken.

Once I bring these materials into my practice, I destabilise them. I reframe them, remix them, scale them up, overlay them, and place them into contemporary dialogues. In the AUSTRALIA series, for example, I take Blandowski and Mützel’s tiny albumen prints and transform them into monumental surfaces. In GABAN, a post-traumatic theatre work (ngarranga-birdyulang dhadharra), I turn archival items into characters with agency: carved trees, photographs, massacre letters, guilt, witness, museum authority and time itself. They argue, remember, revolt and ultimately participate in a fictional repatriation ceremony that reverses institutional power and allows cultural belongings to speak. Through these transformations, I rebuild the relationship between archival objects and living communities — a relationship that museums often disrupted.

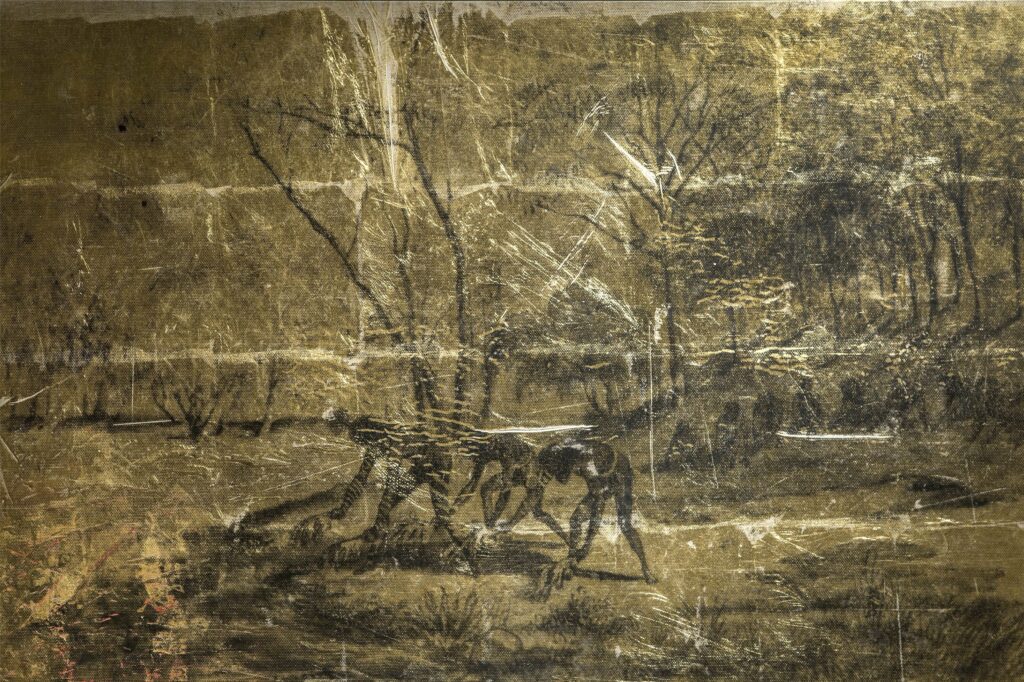

Brook Andrew, Australia III, 2014, Black ink, gold foil on linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

What lines can you draw between archival images and contemporary popular culture?

The colonial image never disappeared; it just changed shape. Many of the stereotypes that circulated in nineteenth-century scientific illustrations and postcards still appear today in film, tourism, advertising, sporting commentary and political rhetoric. They re-emerge in debates about authenticity, in the fetishisation of “traditional Aboriginality,” and in the persistent idea that Indigenous people belong in the past rather than the present. Even something like the early Grook football images — representing an Aboriginal football game played with a possum-fur ball, which I use in Australia I — have been absorbed into the mythology of Australian Rules Football without proper acknowledgment of their Indigenous origins. The archive is not separate from contemporary culture; it is its engine room. Our national identity has been built upon fragments of these images, whether romanticised or dehumanised. My work exposes these echoes. By enlarging historical scenes, making them reflective, or activating them theatrically, I make visible the hidden scaffolding that shapes how Australians continue to see themselves and each other.

Where do your conceptual tools come from?

My conceptual tools come from two intertwined sources: my Wiradjuri worldview and my Western art education. From my family and community, I inherit the ethics of relationality — the understanding that objects, people, land, language and Ancestors are connected through responsibilities and story. From early on, I also inherited the awareness that representation carries power. Who holds the camera, who writes the caption, who stores the object, and who gets to speak. At art school I became drawn to Surrealism and Dada, particularly their strategies for disrupting dominant ways of seeing. I was always making, always drawing, always reshaping the world visually. Later, through theatre scholars and elders, I developed the framework of ngarranga-birdyulang dhadharra, post-traumatic theatre, which allows me to use performance to activate archival trauma and imagine new futures. These tools are not separate; they inform each other. They allow me to dismantle the colonial image, expose the Colonial Wuba, hole, and create pathways for murum-gidyal, healing.

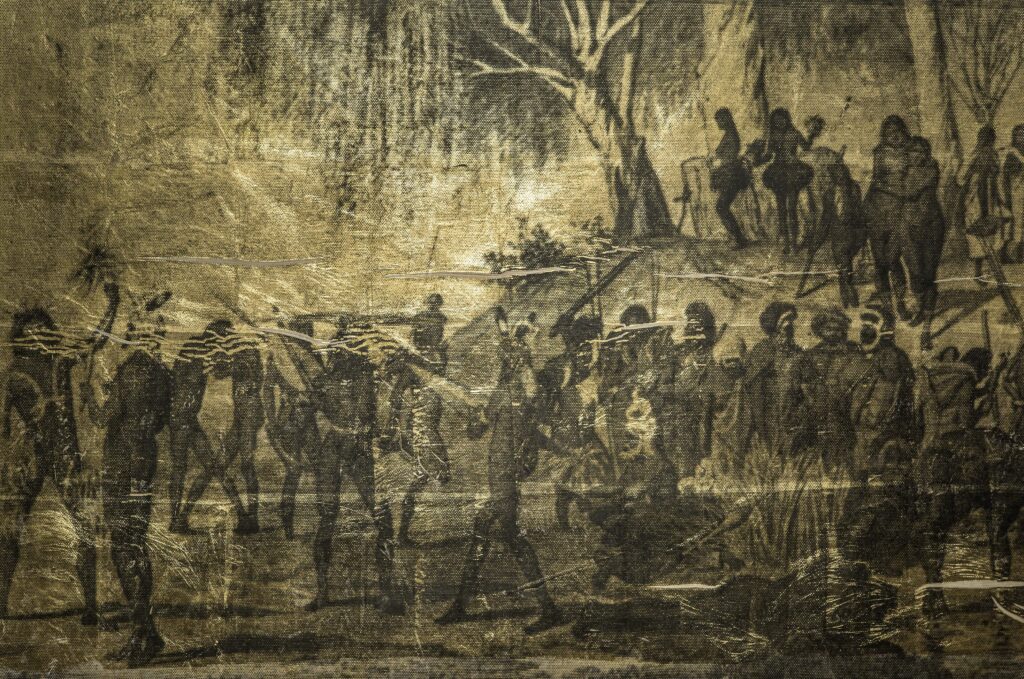

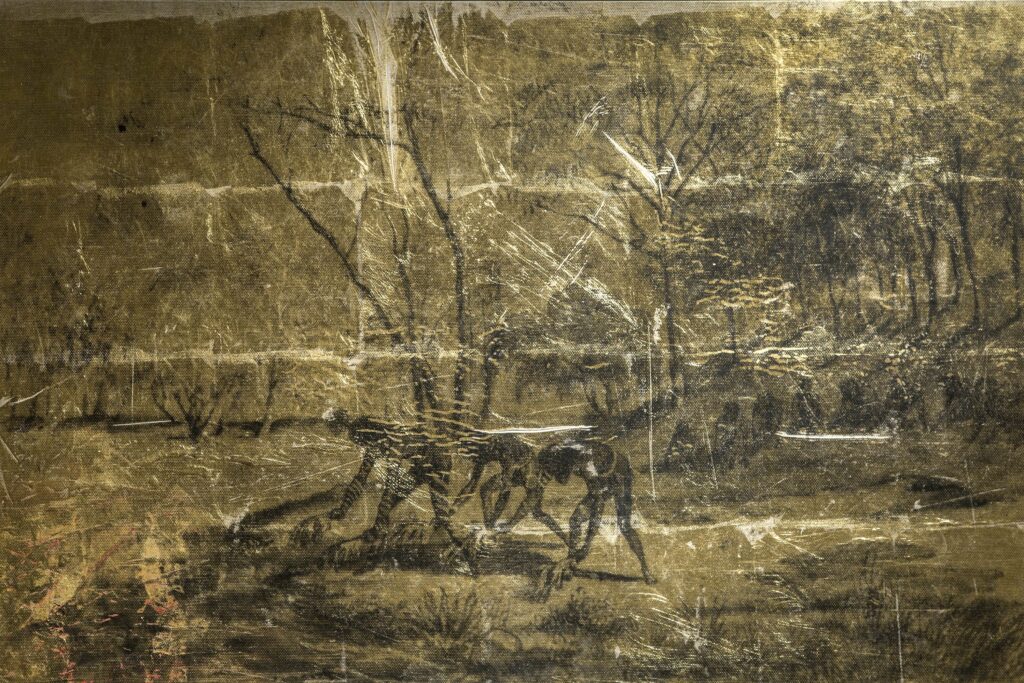

Brook Andrew, AUSTRALIA IV, 2014, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

Why revisit Gustav Mützel’s images in the AUSTRALIA series?

The images in the series sit at a fascinating crossroads of intent, translation, distortion and possibility. Mützel never set foot in Australia; he made illustrations from Blandowski’s sketches and notes. Blandowski, operating within a colonial scientific mission, nevertheless depicted Aboriginal people with a surprising empathy and humanity compared to many contemporaries. Yet, by the time those sketches travelled to Europe, passed through publishers, and landed in the photographic archives of museums, they had become part of the machinery that defined Aboriginal people as ethnographic “types.” I revisit them because they reveal how colonial imagery was constructed — not as a direct encounter but as a chain of translations.

Works in the series, such as AUSTRALIA IV and AUSTRALIA V, carry complex narratives that Europeans often misinterpreted or sensationalised. The scenes depict ceremonial activities, embodied knowledge and social interactions that have deep cultural meaning. Yet, they were reduced to curiosities, aestheticised objects or scientific specimens. I choose to work with these images because they allow viewers to confront their own expectations: Do they want explanation? Ownership? Decoding? The reflective surface denies these impulses. It holds the sacred in place while revealing the distortions of the colonial gaze.

What happens when you re-present these images?

The images destabilise themselves and the viewer. When a small archival image becomes a two-metre shining surface, its authority shifts. The viewer no longer observes from the outside — they are implicated. Their reflection becomes part of the work. This forces them to confront their own position in the ongoing legacy of colonial representation. For the subjects in the images, the shift is equally powerful: they regain scale, energy and presence. They move from being scientific data to powerful cultural actors. Re-presenting these images also reconfigures the archive. It disrupts the idea that archival materials are fixed or neutral. In my work, the archive becomes a living, shifting structure where Indigenous voices and contemporary critique reshape what these images can mean.

Brook Andrew, AUSTRALIA V, 2014, mixed media on Belgian linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

How do scale and surface affect the gaze?

Scale is a political choice — it determines who has visual authority. When an image that was once tiny and tucked into a library shelf becomes monumental, it commands a new level of respect, restores the dignity of their subjects and opens space for new readings. Their scale suggests a form of cultural sovereignty — a pushback against the historical shrinking of Indigenous lives into footnotes or prints. They become almost cinematic, demanding attention and resisting simplification. Thus reframed, the ethnographic subject transforms into a protagonist. The reflective foil surface intensifies this. It brings the viewer into the field of vision, making it impossible to remain invisible. The foil also carries a metaphorical charge: uneven illumination, the glare of “discovery,” the shimmer of projection. It mirrors the instability of colonial knowledge — the way narratives shift depending on who is looking and from where. Scale and surface, therefore, are tools for unsettling and rebalancing power.

Brook Andrew, AUSTRALIA VI, 2014, Mixed media on Belgian linen, 200 x 300 x 5 cm

How do archival works relate to your broader practice?

My work with, in and into archive is the heartbeat of my entire practice. Whether I am making neon works, installations, theatre, sculpture, video or writing, the dialogue with archives and Powerful Objects is constant. My interventions in museums, my curatorial work at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, my leadership of NIRIN, and my development of frameworks like the Colonial Wuba, hole, and ngarranga-birdyulang dhadharra, post-traumatic theatre, all stem from deep archival engagement. Works like AUSTRALIA I, The Island, EVIDENCE, and GABAN are different manifestations of the same project, i.e., to expose the structures that shaped colonial representation, to restore complexity and dignity to Indigenous subjects and to create new spaces — physical, conceptual and ceremonial — for Indigenous futures. The archive is not a dead repository; it is a site of conflict, imagination and healing. Everything I do grows from that understanding.

Ames Yavuz will present AUSTRALIA IV and AUSTRALIA V at Art Basel Miami Beach (Booth E18) from 3-7 December 2025.